Cela faisait pas mal de temps, mine de rien, que je n’avais plus lu de livres de Paul Auster. Une fois la période des partiels terminée, et donc une fois ma liberté de lire ce que je voulais retrouvée, c’est assez naturellement que je me suis décidé pour relire un « vieux » Paul Auster, l’un des premiers que j’ai lu, c'est-à-dire Moon Palace. Je n’en n’avais plus qu’un vague souvenir, quelques images qui restaient ancrées dans ma tête et puis, bien sûr, de bonnes impressions qui demeuraient, un plaisir de lecture difficile à oublier, etc. Finalement, en relisant ce livre parut en 1990, j’en suis venu à le voir d’une façon toute à fait différente.

Il est assez délicat de résumer brièvement Moon Palace car en fait, ce n’est pas vraiment une seule intrigue à part entière, mais plusieurs petites histoires, récits ou anecdotes qui s’enchaînent, s’emboîtent et se croisent. Mais on y retrouve cela dit un personnage clé, c'est-à-dire (comme souvent chez Auster), le narrateur : M.S. Fogg. Le « M » est pour Marco (Polo), le « S » pour Stanley (un journaliste américain à la recherche de Livingstone en Afrique) et « Fogg », en plus de signifier « brouillard » en anglais (« fog » avec un seul « g »), renvoie évidemment au Phileas Fogg du Tour du monde en quatre-vingt jours de Jules Vernes. M.S., au début du roman, vit avec son oncle Victor (sa mère est morte et il n’a jamais connu son père) mais il doit bien vite apprendre à voler de ses propres ailes, ce qui ne lui réussit pas vraiment. Il connaît la misère, il vit dans la rue et manque de mourir dans l’anonymat en plein cœur de Central Park. Ce qui le sauve, en plus de ses amis, sera le travail que lui offre un vieillard handicapé : lui tenir compagnie. C’est un peu rapide, mais l’intrigue générale ressemble à peu près à ça, sachant quand même que le narrateur navigue en fait de mini-histoire en mini-histoire, de personnages en personnages qui prennent tous, à un moment donné, plus ou moins soin de lui.

En fait, Moon Palace est un roman du paradoxe. Paradoxal, il l’est tout d’abord dans son rapport avec son auteur : il s’agit d’un roman purement austerien (allant même parfois presque jusqu’à l’excès) avec le rapport d’opposition New York/grands espaces américains, les déambulations urbaines, le basculement dans la misère, et surtout la quête du père et l’omniprésence constante du couple hasard/coïncidences tout en étant, en même tant, totalement à l’opposé des autres œuvres majeures d’Auster (je pense surtout à Léviathan, Le voyage d’Anna Blume ou encore Mr Vertigo). Car Moon Palace s’éloigne du roman austerien traditionnel, collectant diverses petites intrigues indépendantes pour constituer un seul et même ouvrage. De la même façon, le paradoxe se retrouve dans le « genre » du livre : à priori roman dit « d’apprentissage », Moon Palace se révèle finalement être un anti-roman. Le narrateur est ainsi l’antithèse complète du personnage de roman d’apprentissage dans le sens que non seulement il n’apprend pas mais il n’agit pas non plus et toutes ses décisions sont en fait prises par d’autres personnages (d’où l’impression de loque qui se dégage de ce brave Marco). Il ne fait qu’être trimballé de tuteur en tuteur, peut être pour compenser son absence de père sans jamais devenir indépendant (ou « majeur »). M.S. Fogg, c’est aussi l’antithèse du « héros américain » par excellence : il se désintéresse de la possession, de la consommation, de l’argent et même de l’amour (sa petite amie, Kitty Wu, ne sert pratiquement à rien dans le roman), il n’a pas beaucoup de valeur et il n’est consistant que lorsqu’il est entouré par d’autres (d’où son naufrage lorsqu’il vit en SDF dans Central Park). En fait, ce narrateur est plus une sorte d’incarnation du lecteur qui ne cherche qu’une chose : être pris en charge, qu’on lui parle, qu’on lui raconte des histoires. C’est un personnage lunaire (dans tous les sens du termes compte tenu de l’omniprésence de cet astre dans le roman), toujours dans le brouillard, et qui ne peut se diriger que lorsque quelqu’un est là pour le diriger.

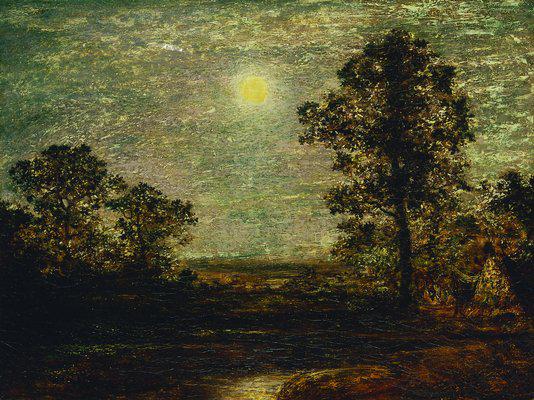

Enfin, Moon Palace, c’est également, en plus d’une succession de petites histoires, un roman de l’ekphrasis (« description d’une œuvre d’art réelle ou imaginaire au sein d’une fiction », j’aime employer ce genre de terme pour donner l’impression que je sais plein de trucs), puisqu’on retrouve en permanence des références artistiques diverses et multiples (le Voyage dans la Lune de Cyrano, un tableau de Blakelock, le premier roman de Julian Barber, etc.) qui servent de miroir au roman (avec la lune comme dénominateur commun). Un des passages les plus réussis contient d’ailleurs la description du Clair de Lune de Blakelock que je vais d’ailleurs vous inviter à lire avec l’extrait qui va suivre. A ce moment là du livre, le narrateur travaille pour le fameux vieillard (Effing), qui lui demande de faire le vide dans sa tête et d’aller contempler le tableau dont il lui parle depuis quelques temps au musée de Brooklyn. Ce tableau constitue en fait un reflet exemplaire de ce qu’est Moon Palace. Je vous laisse avec le texte d’Auster himself et le fameux tableau… (Désolé, je n'ai mis que le texte anglais car j'ai la flemme de taper aussi la traduction de Christine Le Boeuf...)

Then I came to Moonlight, the object of my strange and elaborate journey, and in that first, sudden moment, I could not help feeling disappointed. I don’t know what I had been expecting – something grandiose, perhaps, some loud and garish display of superficial brilliance – but certainly not the somber little picture I found before me. It measured only twenty-seven by thirty-two inches, and at first glance it seemed almost devoid color: dark brown, dark green, the smallest touch of red in one corner. There was no question that it was well executed, but it contained none of the overt drama that I had imagined Effing would be drawn to. Perhaps I was not disappointed in the painting so much as I was disappointed in myself for having misread Effing. This was a deeply contemplative work, a landscape of inwardness and calm, and it confused me to think it could have said anything to my mad employer.

I tried to put Effing out of my mind, then stepped back a foot or two and began to look at the painting for myself. A perfectly round full moon sat in the middle of the canvas (the precise mathematical center, it seemed to me – and this pale white disc illuminated everything above it and below it: the sky, a lake, a large tree with spidery branches, and the low mountains on the horizon. In the foreground, there were two small areas of land, divided by a brook that flowed between them. On the left bank, there was an Indian teepee and a campfire; a number of figures seemed to be sitting around the fire, but it was hard to make them out, they were only minimal suggestions of human shapes, perhaps five or six of them, glowing red from the embers of the fire; to the right of the large tree, separated from the others, there was a solitary figure on horseback, gazing out over the water—utterly still, as though lost in meditation. The tree behind him was fifteen or twenty times taller than he was, and the contrast made him seem puny, insignificant. He and his horse were no more than silhouettes, black outlines without depth or individual character. On the other bank, things were even murkier, almost drowned in shadow. There were a few small trees with the same spidery branches as the large one, and then, toward the bottom, the tiniest hint of brightness, which looked to me as might have been another figure (lying on hiss back—possibly asleep, possibly dead, possibly staring up into the night) or else the remnant of another fire—1 couldn't tell which. I got so involved in studying these obscure details in the lower part of the picture that when I finally looked up to study the sky again, I was shocked to see how bright everything was in the upper part. Even taking the full moon into consideration, the sky seemed too visible. The paint beneath the cracked glazes that covered the surface shone through with an unnatural intensity, and the farther back 1 went toward horizon, the brighter that glow became—as if it were daylight back there, and the mountains were illumined by the sun. Once I finally noticed this, 1 began to see other odd things in the painting as well. The sky, for example, had a largely greenish cast. Tinged with the yellow borders of clouds, it swirled around the side of the large tree in a thickening flurry of brushstrokes, taking on a spiralling aspect, a vortex of celestial matter in deep space. How could the sky be green? I asked myself. It was the same color as the lake below it, and that was not possible. Except in the blackness of the blackest night, the sky and the earth are always different. Blakelock was clearly too deft a painter not to have known that. But if he hadn't been trying to represent an actual landscape, what had he been up to? I did my best to imagine it, but the greenness of the sky kept stopping me. A sky the same color as the earth, that looks like day, and all human forms dwarfed by the bigness pf the scene—illegible shadows, the merest ideograms of life0 I did not want to make any wild, symbolic judgments, but based on the evidence of the painting, there seemed to be no other choice. In spite of their smallness in relation to the setting, the Indians betrayed no fears or anxieties. They sat comfortably in their surroundings, at peace with themselves and the world, and the more I thought about it, the more this serenity seemed to dominate the picture. I wondered if Blakelock hadn't painted his sky green in order to emphasize this harmony, to make a point the connection between heaven and earth. If men can live comfortably in their surroundings, he seemed to be saying, if they can learn to feel themselves a part of the things around them, life on earth becomes imbued with a feeling of holiness. I was only guessing, of course, but it struck me that Blakelock was painting an American idyll, the world the Indians had before the white men came to destroy it. The plaque on the wall noted that the picture had been painted in 1885. If I remembered correctly, that was almost precisely in the middle of the period between Custer's Last Stand and the massacre at Wounded Knee—in other words, at the very end, when it was too late to hope that any of these things could survive. Perhaps, I thought to myself, this picture was meant to stand for everything we had lost. It was not a landscape, it was a memorial, a death song for a vanished world.

Comme mon billet est déjà assez long je vais m’arrêter là. Moon Palace n’est sans doute pas le meilleur Auster, mais il s’agit d’un livre déroutant, à la fois 100% Auster et assez éloigné de ce qu’il a pu écrire parla suite. Il ne plaira sans doute pas à tout le monde, je le conçois tout à fait, donnant parfois l’impression de parler pour ne rien dire et de raconter des histoires parallèles pour mieux éviter de raconter l’histoire principale. Certaines parties sont, de plus, assez maladroites (la relation de M.S. avec Kitty Wu, par exemple) mais je le conseille tout de même, ne serait-ce que pour pouvoir lire, lors de la dernière page (ce n’est pas un spoiler, promis), une phrase assez « osée » compte tenu du fait qu’on vient de se farcir plus de trois cent pages auparavant : « This is where I start, I said to myself, this is where my life begins », comme si tout ce qui s’était passé avant n’avait finalement aucune importance. Mais ce n’est pas grave, car comme tous les livres de Paul Auster, Moon Palace maintient un univers fascinant de la première à la dernière page et c’est bien tout ce qui importe.